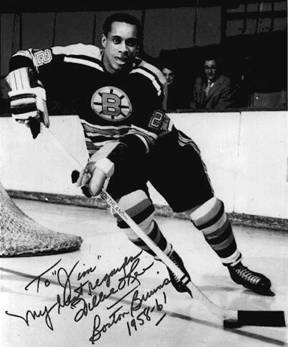

Soul on Ice: The Willie O'Ree Story

by Mike Walsh

In

1958 a young man named Willie O'Ree made his debut in the National Hockey

League. He was with the Boston Bruins for two games. After two more years

in the minors, O'Ree had a longer stay with the Bruins--41 games. After

that, O'Ree never played another game in the NHL.

In

1958 a young man named Willie O'Ree made his debut in the National Hockey

League. He was with the Boston Bruins for two games. After two more years

in the minors, O'Ree had a longer stay with the Bruins--41 games. After

that, O'Ree never played another game in the NHL.

This may not seem particularly significant, but O'Ree was different from every other NHL player who had come before him during the league's first 50 years. He was black, and there wouldn't be another black player in the NHL for 25 years.

Hockey was about 10 years late when it came to integration. All other professional sports, including tennis, bowling, golf, baseball, football, and boxing, were racially integrated by 1950. Hockey was the holdout. It was the whitest sport. There were no black players, coaches, team owners, or sportswriters.

Boxing was the first to integrate with black champs Jack Johnson and Joe Louis dropping one Caucasian after another during the first half of the century.

Jackie Robinson integrated baseball to great fanfare in 1947, but O'Ree's breakthrough hardly merited a mention. O'Ree did not appear on the nightly news. The New York Times, for example, did not find it newsworthy. Since Canada didn't have the racial strife that plagued the U.S., no one called much attention to O'Ree.

O'Ree played successfully in the minors until the mid-1970s, and he won numerous scoring titles. To this day, he is regarded as a footnote in the world of sport. The hockey encyclopedias give him only passing reference, if any at all.

O'Ree was born in 1935 and grew up in Fredericton, New Brunswick, a small city in coal mining region just north and east of Maine.

"In the city where my family lived, there were probably only two or three black families," says Willie. "Most of the black families lived on the outskirts of town. In retrospect, I think my living around whites made me feel I could play in the pros. I always knew I was as good or better than they were."

He started skating when he was three years old and began playing in a league at age five. "That was the thing to do in the winter," he says. "Everything freezes over, the ponds, rivers, creeks. Every chance I had, I was on the ice. I even skated to school. My Dad squirted the garden hose on the back yard, and we had an instant rink."

Willie played in local hockey leagues before joining a junior team while in high school. The juniors in Canada roughly equate to college hockey teams in the U.S.

Willie was also a heck of a baseball player. "I was a pretty good shortstop and second baseman. In 1956, I was invited to the Milwaukee Braves minor league facility in Waycross, Georgia. I told them that I planned to make hockey my career and that I had no interest in becoming a professional baseball player. I played baseball in the summer just to keep my legs in shape and to keep my reflexes sharp. They talked me into going anyway. I was in Georgia for about three weeks. I had a good camp, but I was afraid I would catch on and it would interfere with my hockey, so I left.

"That was my first time in the south. Its customs, you know--like white-only or colored-only restaurants. I never experienced anything like that in Canada. When I left, I had to sit in the back of the bus. I couldn't move to the front until I got up north."

During the 1955/1956 hockey season, Willie played for the Kitchener-Waterloo Canucks, a junior league team. During a game he was struck with a puck in the right eye. The injury was so serious that he permanently lost 95% of the vision in that eye. A doctor advised him to stop playing, but that was inconceivable to Willie. In eight weeks he was back on the ice.

He had only one problem. "Being a left wing, my right eye was closest to the puck. When I came back, I would loose sight of the puck, and I was getting body checked much more. So I switched to the right side. I had to take most of the passes on my backhand, but it didn't bother me. At least I had vision of the rink."

Willie turned pro the next season when he signed with the Quebec Aces, a minor league team affiliated with the Boston Bruins. He signed for $3,500 with a $500 signing bonus. That year the Quebec Aces won their league championship.

Willie spent a few weeks at the Bruins training camp before starting the next season in the minors. One of his coaches told him, "Willie, you could be the first of your race to make it to the NHL. You got everything it takes. You can skate, shoot, you're strong, you're diligent."

That winter the Bruins roster was depleted by injury, and the team found itself especially short at winger. Willie got the call. On January 18, 1958, in Montreal, Willie took the ice with the Boston Bruins, becoming the first black player to make it to the NHL. The reaction to Willie's achievement was decidedly underwhelming.

"I was expecting a little more publicity. The press handled it like it was just another piece of everyday news. I didn't care that much about publicity for myself, but it could have been important for other blacks with ambitions in hockey. It would have shown that a black could make it."

He played another game in Boston before returning to the Quebec team. Willie toiled in the minors the next two years and continued to improve, despite being legally blind in one eye. From what he knew, the Bruins weren't aware of the his disability.

He was called up again by the Bruins in 1961, and he finished the year with the team, playing in 43 games and scoring a modest 4 goals and 10 assists.

Life in the NHL wasn't easy for a black player. "Guys would take cheap shots at me, just to see if I would retaliate," he says. "They thought I didn't belong there. When I got the chance, I'd run right back at them. I was prepared for it because I knew it would happen. I wasn't a great slugger, but I did my share of fighting. I was determined that I wasn't going to be run out of the rink."

The intimidation erupted into full-scale donnybrook one night in Chicago. "I was behind the Chicago net, and I passed the puck out front. Eric Nesterenko came around on my blind side and butt-ended me in the face with his stick. He knocked out two of my teeth and broke my nose. Blood was squirting out all over. I knew he did it on purpose, so I hit him over the head with my stick. Nailed him above the right eye. Back then the players didn't wear helmets. Both benches cleared. They had to put 15 stitches in his head."

It wasn't just opposing players he had to contend with. "Racist remarks from fans were much worse in the U.S. cities than in Toronto and Montreal. I particularly remember a few incidents in Chicago. The fans would yell, 'Go back to the south' and 'How come you're not picking cotton.' Things like that. It didn't bother me. Hell, I'd been called names most of my life. I just wanted to be a hockey player, and if they couldn't accept that fact, that was their problem, not mine."

Willie was known mostly for his speed. His coach in Boston, Milt Schmidt, said that Willie "was one of the fastest skaters in the NHL."

"My speed was an asset. I could be standing still and then take four or five strides and be at top speed." Willie's specialty was charging up the ice, shooting into a seam in the defense, taking a pass, and shooting. If the timing was right, it was a deadly offensive play.

Willie's happiest moment in the NHL came in 1961 in a game at the Boston Garden on New Year's night. "We were playing the Montreal Canadians. It was late in the third period. I received a pass and was sweeping around the Montreal defense. I took a low shot, keeping the puck along the ice, and it slid into the corner. It turned out to be the winning goal. The fans gave me a two-minute standing ovation. It was a nice feeling."

During the season, Milt Schmidt, the Bruins coach, told reporters, "Willie's got all the equipment a good professional needs and some splendid natural advantages... I hope he'll be with us a long time."

At the end of the season, Schmidt and Lynn Patrick, the general manager had a talk with Willie. "They said, 'Go home and have a good summer. We're impressed with your play. You'll be back with the Bruins."

Willie went home to Fredericton. His future looked bright. His friends and relatives were excited for him. But six weeks later he got a call from a sportswriter asking him what he thought of the trade. Willie's contract had been sold to the Montreal Canadians, and the Bruins hadn't bothered to inform him. Willie was stunned.

"Considering the talent Montreal had, I knew I had no chance of making their squad. So I wasn't surprised when I was assigned to their Hull-Ottawa minor league affiliate. I never did get any information from the Bruins on why the move was made."

To this day, the episode is Willie's bitterest memory.

Within

two months, Willie was again traded to the Los Angeles Blades of the Western

Hockey League.

Within

two months, Willie was again traded to the Los Angeles Blades of the Western

Hockey League.

"At that point, I was 26 or 27 and figured my hopes of ever making it to the NHL were small, but I still loved to play."

Willie played the next six seasons for Los Angeles and won the league goal scoring title in 1964 with 38 goals.

When the NHL expanded to twelve teams in 1968, Los Angeles got one of the franchises and the Los Angeles Blades folded. Willie's contract was purchased by the San Diego Gulls. The Gulls management told Willie they were glad to have him on the team instead of scoring goals against them, as he had with the LA team.

Willie enjoyed the dedicated San Diego fans. "They were averaging 9,000 to 10,000 fans per game. The place was just rockin'."

Willie won the WHL goal scoring title again in 1969 at the age of 34 with 39 goals.

The Western Hockey League folded in 1974, and Willie retired. He had fallen in love with San Diego and its warm weather, so he settled there. He managed fast food restaurants and sold cars.

In 1978 another team was put together in San Diego as part of the new Pacific Hockey League. The San Diego Hawks invited Willie to join the team. Willie had been keeping himself in good shape, so at age 43 he laced up the skates one more time. Incredibly, Willie missed only a half-dozen games of the 70-game season and scored 50 points. It was his last hurrah.

Willie's highest yearly hockey salary was $17,500. That was late in his career at San Diego. Even that didn't seem fair. Many of the players on the San Diego team were paid almost double that amount because they were owned by NHL teams.

Willie now lives and works in San Diego. He no longer plays hockey or even skates. One of his knees was so worn down that two years ago he had a total knee replacement.

Willie isn't sure why he didn't have a longer career in the NHL. "If I hadn't gotten that eye injury," he says. "To this day a lot of people don't realize that I played my entire 20-year pro career with one eye."

He's not sure if the NHL was discriminatory, but he has cause for suspicion. "There were blacks in the minor leagues and good ones too. The Quebec Aces had a history of having black players. Before my time, they had an all-black line with the Carnegie bothers, Herbie and Ossie, and Manny McIntyre. You talk about three players who were good, stick handling, passing, shooting--you name it, they could do it. But they never got a chance. Not one of them was ever called up."

Incredibly, it took 25 years for another black to make it to the NHL, and the situation today remains much the same today. Thirty-eight years after Willie O'Ree broke the racial barrier in pro hockey, minority players are still rare in the NHL. Part of the reason is that blacks and other minorities don't make up a significant portion of the Canadian population, and few African Americans take up the sport in the U.S.

Overall, Willie looks back fondly on his hockey career. He is proud "not just to be the first black in the NHL, just to play in the NHL. They called me the Jackie Robinson of hockey, but I didn't have the problems he had. I was never refused service at a hotel or restaurant, and I was accepted by my teammates."

If

he had played in today's NHL with its 26 teams, instead of when the league

had only six teams, Willie might've become a rich and famous star. If

ever a player deserved that kind of success, it was Willie O'Ree. He was

the polar opposite of today's sports stars--polite, reserved, dignified,

and well-spoken. He didn't yell at referees, dance for the fans, or taunt

opponents. He was given a taste of the pro sports life, but he never got

a real chance. And, sadly, he wasn't the only one.

If

he had played in today's NHL with its 26 teams, instead of when the league

had only six teams, Willie might've become a rich and famous star. If

ever a player deserved that kind of success, it was Willie O'Ree. He was

the polar opposite of today's sports stars--polite, reserved, dignified,

and well-spoken. He didn't yell at referees, dance for the fans, or taunt

opponents. He was given a taste of the pro sports life, but he never got

a real chance. And, sadly, he wasn't the only one.

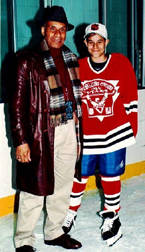

The most fitting tribute to Willie's career came recently when the NHL created an all-star game for young minority hockey players and named it in Willie's honor. The Willie O'Ree All-Star Game is held every year at the World Junior Championships.

UPDATE: On January 17, 1998, during ceremonies before the NHL All-Star game, the NHL honored Willie O'Ree for his pioneering efforts and named him the director of youth hockey development for the NHL/USA Hockey diversity task force. He will travel all over North America helping to establish programs.

"We're going to reach out and get into the neighborhoods where these ethnic kids and families live," Willie said. "Our job is to help these kids along, help them with their skills, hockey skills and other life skills, to make sure they're heading in the right direction. Hopefully I can make a difference, and we'll see more minority players get into the NHL.''

Back to: [top] [MouthWash] [missionCREEP]

outh

outh ash

ash